who needs ribs when it comes to curves?

- costumechronicle

- Feb 6, 2024

- 14 min read

Updated: Feb 8, 2024

Exploring the aesthetics of corsetry through ages

In the grand tapestry of fashion history, there's a garment that has cinched its way into the hearts, and sometimes the breath, of wearers throughout the ages:

THE CORSET!

This journey through time isn't just about laces and stays; it's a captivating saga of allure, rebellion, and the age-old dance between fashion and feminism. So, buckle up (or should I say, lace up?), as we traverse the fascinating landscape of the corset, where fashion meets the fine line between allure and, well, taking your breath away... literally.

William Heath, ca.1830. A Correct View of The New Machine for Winding Up The Ladies

Corsets were worn by women (as well as by men in rare situations) across the Western world from the late Renaissance until the 20th century.

Was it considered a "torturous contraption," a significant contributor to poor health, and even a cause of death?

Many women purportedly engaged in "tight-lacing," striving for waist measurements of less than 18 inches simply because "extraordinary thinness was demanded, with a 13-inch waist measurement being the benchmark for societal allure. This practice supposedly led to the compression of their ribs and internal organs.

Why did women wear corsets?

Did the use of corsets serve as a drastic mechanism, enabling a male-dominated culture to exercise authority over women and manipulate their sexuality for societal control?

The corset, like a sneaky chameleon, has slithered through history, shaping not just silhouettes but also stirring up debates about control and individual expression. The historical role of corsets is complex, and opinions on whether they were used as a mechanism to control and manipulate women's bodies and sexuality vary among historians and scholars.

Societal expectations placed a strong emphasis on modesty, and corsets were considered a symbol of refinement and femininity. Some argue that the restrictive nature of corsets reflected the societal norms and expectations imposed on women.

On the other hand, it's crucial to note that women's fashion, including the use of corsets, has often been shaped by a combination of societal, cultural, and aesthetic factors. While corsets could be seen as a reflection of societal control, they were also embraced by some women as a means of expressing their own identity and conforming to beauty standards of their time.

Several sources propose that women wear corsets with the goal of achieving a slim waist, which was considered a significant standard of beauty. Additionally, the prioritization of social status and respectability outweighed the significance placed on comfort.

Using corsets was a contextual method with varied interpretations for different individuals across different periods. While some women perceived the corset as a bodily intrusion, it also held numerous positive associations, such as societal position, personal control, creative expression, dignity, aesthetic appeal, and sensual attraction.

The corset had its beginnings many centuries earlier within the courtly circles of the aristocracy, later extending its influence across society to encompass women of diverse backgrounds or lower class in addition to those in positions of privilege.

Women, spanning various social strata, donned diverse types of corsets, fastening them with varying degrees of tightness and for different purposes. Consequently, the corporeal encounter with corsetry displayed notable differences among women.

The history of the corset spans several centuries and is intertwined with changes in fashion, societal norms, and cultural influences. Let’s dive in the timeline highlighting key points in the evolution of the corset:

Ancient Creations (2000 BC - 300 AD)

Early corset-like garments can be traced back to ancient civilizations such as Crete, where women wore tightly fitted bands to accentuate the waist.

Historical records indicate that the Minoans, residing in Crete around 1000 BC, were pioneers in donning corset-like attire. The earliest representation of a corset can be traced back to a figurine portraying the Minoan snake goddess adorned in a corset-like garment. Artifacts from Minoan artwork further support the idea that both men and women utilized such garments.

The Minoans were among the early adopters of corset-like apparel, a straightforward piece made from linen or wool, encircling the midsection and secured tightly to achieve a slenderizing appearance. This body-shaper functioned as an outer garment, primarily reserved for ceremonial occasions rather than everyday wear.

The subsequent instances of corset-like garments trace back to ancient Greece. Crafted from linen or wool, these pieces were intricately tailored to tightly encircle the waist. Women utilized bands made of linen or leather to emulate the coveted hourglass figure. Known as a "Zone," this belt-style fabric bore cultural significance as a symbol of sexual maturity. Unmarried adult women adorned a belted variation of the Zone to denote virginity, emphasizing its role in cultural norms and gender structures. The removal of these Zones on wedding nights, typically done by their husbands, held symbolic importance. These Zones were worn tightly, only loosened during pregnancy and childbirth. Often crafted from linen or wool, these corset-like pieces featured embellishments like gold or silver threads and beadwork.

In Ancient Rome, women also embraced band-like garments known as “Strophium” or “Mamillare”, which provided support and shaping for their breasts, representing an early form of shapewear. Various cultures have created diverse forms of waist-cinchers and bust-bodies, often regarded as precusors to the corset.

However, there appears to be a lack of significant cultural continuity among these ancient garments, charaterized by the use of draped rectangular pieces of cloth, and the European corset that emerged during the Renaissance in Italy and Spain.

Minoan Snake Goddess figurines, c. 1600 BCE, Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete

Medieval Europe (12th - 16th centuries)

Historians remain uncertain about whether women wore corsets during the early medieval period. There are some indications, such as the narrow-waisted dresses, making it challenging to envision them without corsets. It is likely that instead of a separate garment, bones or wooden slats were incorporated directly into the attire.

Additionally, a 12th-century illustration of a demon wearing a corset has been suggested as evidence.

“Popular histories of the corset often reproduce a picture of the so-called “fiend of fashion”, a demon in “an ancient manuscript” who is dressed as a woman in a laced bodice resembling a corset” (Valerie Steele, The Corset, A Cultural History)

In the middle age, dresses were tailored tightly to define and slim down the waist significantly. The revived preference for slender figures gave rise to the distinctive corsage style known as Cotehardie (or Kirtle). These were heavily reinforced and worn extremely snug, serving as an outer garment in contrast to corsets.

Ladies in Cotehardie

By the 15th century, fashionable European women frequently adorned dresses that were laced closed, aiming to achieve a tighter fit and highlight the bosom, marking a precursor to the corset.

According to Valerie Steele, “The other precursor of the corset was the basquine or vasquine, a laced bodice to which was attached a hooped skirt (farthingale). The vasquine apparently originated in Spain in the early sixteenth century and quickly spread to Italy and France.” (The Corset: A Cultural History)

As opulent fabrics like heavy silk brocade and velvet gained prevalence among the elite, dressmakers shifted their focus to crafting separate bodices and skirts instead of one-piece gowns. Emphasizing the importance of well-fitted clothing, there was a growing recognition of the ease of fitting garments over a firm foundation.

Contrary opinions among experts arise regarding whether vasquines or basquines were true corsets. Some argue that these garments, with Spanish origins, were styles of petticoats or kirtles, typically comprising a skirt with an attached bodice. It's conceivable that the bodices of these garments were stiffened with bents or whalebone, especially towards the end of the sixteenth century. However, they don't align with the true definition of corsets.

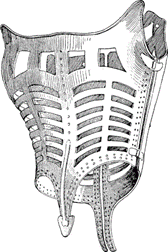

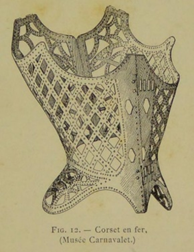

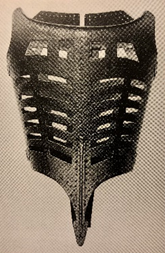

In museum collections, there are indeed specific iron corsets typically attributed to the years 1580 to 1600, raising the question of whether they were the initial fashionable corsets. Upon examination, historians are inclined to believe that these metal corsets were likely designed as orthopedic devices for correcting spinal deformities, and there is no evidence suggesting that women wore them as bodices. Metal corsets, also referred to as iron corsets, represent a historical style of corset or bodice constructed entirely from metal, typically iron or steel. While it was once widely asserted that Catherine de' Medici introduced the metal corset to France in the 16th century, this claim is now regarded as a myth.

Left to right: Fg.1.: Musée de Cluny, Fg.2 Musée Carnavalet, Fg.3: Musée Nationale de Moyen Age, Fg.4: Museum of FIT

16th Century: Origins in Italy and Spain

The corset can trace its origins back to the 16th century, with early versions appearing in Italy and Spain.

Initially, the corset served a functional purpose, providing support for the bust and shaping the torso.

During the Renaissance, stays gained popularity and became a notable fashion accessory for women across various social classes. The structured garments from the 18th century and earlier are commonly referred to as stays. However, by the end of the 18th century, the term "corset" came into use. While "stays" described the rigid, fully boned garment creating the inverted triangle shape, the term "corset" or "corsette" indicated a supportive garment with lighter boning or quilting. The term "corset" has its roots in the Old French word "cors," meaning body, emphasizing the garment's intent to conform more closely to the natural body shape.

The first and best known example of a 16th century corset is the German pair of bodies buried with Pfaltzgrafin Dorothea Sabine von Neuberg in 1598

Stays transformed the torso into a stiff, inverted cone, elevating and supporting the bust while providing a robust foundation for draped garments. Although the terms are commonly used interchangeably today, it is considered more accurate to differentiate between the pre-1800 and post-1800 shapes by using "stays" and "corset."

These corsets were frequently reinforced with boning, and a busk made of wood, horn, whalebone, metal, or ivory further fortified the central front, promoting an upright posture.

Corsets, tracing their origins to the early sixteenth century, marked a significant shift when aristocratic women embraced "whalebone bodies." Essentially, these were cloth foundations evolving to incorporate sturdier materials like whalebone, horn, and buckram. This trend likely emerged in Spain or Italy and quickly spread across Europe. The early corsets, known as whalebone bodies or "corps à la baleine," featured a crucial "busk" at the center front, blurring the distinction between the physical body and the garments that shaped and covered it. This underscored the implicit emphasis on the body, particularly the female body, as a meaningful site.

During the sixteenth century and beyond, corsets primarily adorned aristocratic women. Stays, whether closed or open, served diverse purposes – they could be decorative or plain, worn as underwear or outerwear. Closed stays were laced at the center back, while open stays featured front lacing concealed by a decorative stomacher. The stomacher, integral to women's gowns from approximately 1570 to 1770, took the form of a lengthy V- or U-shaped panel adorning the front of a woman's bodice, extending from the neckline to the waist. It could either be part of the bodice or a separate garment fastened with ties, serving the dual functions of embellishment and structural support.

17th Century: Spread in Europe

The popularity of the corset spread across Europe during the 17th century.

It became a common undergarment for women of various social classes, although the materials and embellishments used often reflected one's social status.

During the 17th century, corsets predominantly consisted of bones and linen, incorporating materials such as reeds and whalebones. Hemp or linen thread was commonly used for crafting the laces. Both men and women embraced corsets during this period, with some featuring attached sleeves, and the lacing becoming increasingly ornate, occasionally enhanced with ribbons for added flair. In this era, the corset transformed into a fabric bodice fastened over a heavily boned core.

1660-1670, The Victoria and Albert Museum

The front of the corset featured a long, pointed busk, while the back was laced. Historical records indicate health issues among young girls who engaged in "tight lacing" to adhere to fashion trends. Subsequently, dresses were boned, suggesting that women wore corsets in conjunction with a boned dress.

By the seventeenth century, girls as young as two years old wore miniature corsets. These were intended to provide support to the body, prevent skeletal deformities, and shape a pleasing waist and well-positioned bust. The training for this began in infancy, aligning with the notion expressed in a sixteenth-century text: "A young tree, if kept straight and bent, maintains the same shape as it grows!" Additionally, young boys were also kept in stays until the age of six.

18th Century: Rise in France and England

The 18th century saw the corset become a prominent fashion item in France and England.

Corsets were worn by women from different social backgrounds, but they were particularly associated with the upper classes.

The prevailing corset style in the 1700s took on an inverted conical shape, often worn to establish a contrast between a rigid quasi-cylindrical torso above the waist and voluminous, heavy skirts below.

During the eighteenth century, stays underwent significant development as a product of intense labor. Staymaking, a predominantly male industry, achieved a remarkable standard by the mid-eighteenth century. Crafted from baleen, commonly known as whalebone and sourced from the mouth of the Right Atlantic Whale, this material was both firm and flexible, allowing it to be cut into thin pieces without sacrificing strength. The stays of the eighteenth century were meticulously constructed by stitching carefully measured strips of whalebone between a lining and facing fabric. Innovatively, whalebone strips were inserted horizontally across the bustline and vertically, creating a rounded opening at the top of the stays. Stays could be either fully boned or half-boned, with the latter being more prevalent in the latter half of the eighteenth century.

1740-1760, The Met Museum Collection

In the eighteenth century, fashion shifted towards a simpler and looser dress style, coinciding with the introduction of the term "corset." By the 1770s, fashionable French women embraced the "corset," described as "a small pair of stays typically made of quilted linen without bones, fastened in the front with strings or ribbons and worn casually." Women began rejecting the perceived elegance of a rigid and tightly cinched waist. While traditional stays persisted for formal occasions and at court, they coexisted with lightweight and flexible corsets that started to replace the conventional stays.

Late 18th Century, The Met Museum Collection

During the reign of Louis XVI, there was a brief period when the neckline and stomacher were positioned beneath the breasts, concealed by a transparent fabric ruffle known as a fichu. This arrangement allowed for the possibility of rouging or even piercing the nipples, adorning them with pearls or other gemstones.

Examples for Fichu from 1790 and1793 (The Met Museum Collection)

The French Revolution didn't solely bring about the decline of stays; their popularity had already waned before 1789. Revolutionary politics, particularly in France, where aristocratic styles were frowned upon, played a role in this decline. The prevailing sentiment advocating "liberty and equality" also contributed to the loosening of whalebone stays. In England, long and heavily boned stays persisted, closely linked with respectable sexual morality. Nevertheless, boneless or lightly boned corsets, bust-bodices, and similar garments gained popularity, particularly in France.

During the era of Neoclassicism, some women adopted a proto-brassiere inspired by the bust-bodices of ancient Rome.

19th Century: Victorian Era

The Victorian era is often synonymous with the corset.

Women from all social classes wore corsets, as they were considered essential for achieving the fashionable silhouette of the time.

In the complex social landscape of the nineteenth century, women, to adhere to societal norms of decency, found it necessary to wear corsets. Victorian women were cognizant of the corset's role as an enhancer of female sexual allure. Additionally, the corset was intended to enhance women's beauty by concealing physical features considered less than ideal. The advent of the Industrial Revolution widened access to corsets, making beauty a perceived right for all women. As the socioeconomic and political structure evolved, the concept of the aristocratic body transformed into a feminine ideal applicable to women across different social classes.

1825-35, The Victoria and Albert Museum

1864, The Victoria and Albert Museum

By the 1820s, the popularity of high-waisted gowns waned, leading to the resurgence of corsets and the elaborate, structured gowns associated with the Victorian era. Concurrently, industrialization in the garment industry resulted in the gradual replacement of classic whalebone stays with steel stays by the 1830s. The introduction of steel boning, along with metal clasps and eyelets, allowed these corsets to be tightened much more than their 18th-century counterparts.

The Victorian era marked the pinnacle of corset popularity, as the waistline returned to its natural position in the 1830s, serving both functional and aesthetic purposes. The coveted hourglass silhouette became fashionable, prompting the design of corsets with whalebone, steel, or reed boning, tightened using lacing. Corsets featured a flat front and a curved back, often adorned with frills, lace, and bows.

Victorian corsets aimed to create the illusion of a smaller waist compared to the hips, achieved by pressing down the floating ribs and compressing the stomach. These corsets were frequently elaborate, boasting finely stitched boning tunnels, luxurious silk brocade, and gold trimmings. Nineteenth-century innovations, such as metal eyelets and steam-molding on metal forms, facilitated tighter lacing, replacing traditional thread-sewn eyelets and allowing mass production without the need for individual measurements.

1890, The Victoria and Albert Museum

20th Century: Decline in Popularity

The early 20th century saw a decline in the popularity of corsets, partly due to changing fashion trends and evolving notions of women's roles.

Corsets were gradually replaced by more flexible undergarments, such as girdles and bras.

Edwardian Corsets and Changing Trends

The Edwardian corsets marked a departure from the previous Victorian designs, aligning with the more liberating nature of Edwardian clothing compared to the rigid Victorian gowns.

The "S" shape corset, pioneered by French corsetiere (who also studied medecine) Inez Gaches-Sarraute, aimed to avoid discomfort and internal injuries. Despite being less costrictive to internal organs, this corset led to various health issues, particularly back problems.

Post-1907, the wasp waist diminished and corsets evolved into a longer, slimmer silhouette with elastic gusset inserts for enhanced comfort. The period from 1908 to 1914 saw a shift to narrow-hipped and narrow-skirted silhouettes, influencing corset lengthening and changes in hip position. As bras gained popularity in the 1910s, corsets with bust support declined, and a new style covering thighs emerged, predicting the 1920s "flapper" silhouette. With the advent of rubberized elastic materials in 1911, girdles began replacing corsets.

Corset, 1908-1910, The Victoria and Albert Museum

Transition from Corsets to Girdles

The popularity of bras increased, leading to a decline in corset during World War I as women supported the war effort. The "mono-bosom" effect of straight-front corsets prompted the addiction of padding. Changes in Edwardian clothes, emphasizing straight silhouette and slim hips, made corsets less practical, and girdles emerged as a more funtional solution. The shift from whalebone corsets to more flexible girdles spanned the twentieth century. Despite a focus on diet and exercise, some form f foundation garment remained integral to women's wardrobes until the 1960s. In recent years, corsets have reappeared in fashion, transitioning from underwear to outerwear.

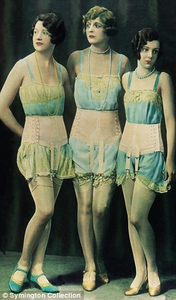

1920s Flapper Corsets

In the 1920s, Flapper corsets departed from the hourglass figure, adopting a more rectangular, straight look in women's fashion. For curvy women, undergarments were employed to achieve te new straight-line aesthetic, stiffening the bodice with boning and tight lacing. The La Garçonne look postwar popularized a boyish, column-like figure, influencing cylindirical, elastic corsets with garters for greater freedom of movement, especially for dancing. Designers like Paul Poiret played a role in promoting a "corsetless" figure, and while traditional corsetry did not dissapear, it evolved with new types of corsets, incorporating stretch fabrics and manufacturing techniques for enhanced support, flexibility, and comfort.

Brassiere, 1929, The V&AMuseum

1930s Beauty and Foundation Evolution

The 1930s witnessed a desire for a fitted, slender silhouette, with women emphasizing laced

and featherlight boned corsets to achieve a shapely frame associated with health. The era introduced panty-girdles in 1935 for use under trousers, and technical advancements like Lastex, a two-way stretch fabric, revolutionized corsetry. With the Great Depression and World War II, utilitarian attire favored boxiers cuts and hanging silhouettes. However, those rejecting this modernistic fashion turned to neo-Victorianism for escapism during the Great Depression. Post-war, corsetry gained prominence with Christian Dior's New Look in 1947,marking a return to extravantly romantic and ultra-feminine fashion.

Left to right: 1. Al Heshfeld Corset Shop, c.1936 , 2.Advertisement from 1949, 3&4. Corset, 1930s, The Victoria and Albert Museum

Brassieres, from 1930s, The V&A Museum

1950s1970s Shifts in Attitude

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, most women wore body-shaping foundation garments, believed to preserve a youthful figure. The late 1960s and early 1970s witnessed a shift away from "control garments" towards alternative forms of body-shaping such as diet and exercise. Girdles and brassieres were increasingly perceived as restrictive and uncomfortable, influenced by the Hippy subculture and feminist movement. The 70s and 80s saw a modern revival with designers like Jean Paul Gaultier and Vivienne Westwood incorporating corsets into their designs. Madonna famously wore corsets during her Blonde Ambition Tour. As diet and exercise, and cosmetic procedures gained popularity, the corset took on new roles in fashion, reimagined as a symbol of female sexual empowerment.

Left to right: Corset 1950s, The V&A Museum; Bra & Suspender Belt, 1960, V&A Museum

Left to right: Jean Paul Gaultier, 1990, The Museum at FIT; Jean Paul Gaultier, 1990, Madonna; Vivienne Westwood, 1990, V&A Museum

Hussein Chalayan, 1998; The Museum at FIT

Revival and Contemporary Use

While traditional corsets are no longer a daily undergarment, there has been a revival of interest in corsetry in the form of fashion corsets and waist trainers.

In modern times, corsets are often worn as fashion statements, costumes, or lingerie rather than as everyday items.

Although corsetry has never truly disappeared, its resurgence is a recurring phenomenon with each revival introducing variations. According to Valerie Steele, the director and chief curator of the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, the depiction of corsets in films or TV shows consistently sparks renewed interest. The transition from being associated with pornographic imagery to a mainstream fashion item is notable. This shift prompted individuals to wear corsets, girdles, and brassieres over their clothing, subsequently giving rise to the trend of incorporating underwear as outerwear. Presently, corsets are more adaptable, available in diverse shapes, sizes, and fabrics, ensuring a comfortable wearing experience without the historical discomfort.

Left to right: Jean Paul Gaultier, 2023; Stella McCartney, 2015 (V&A Museum); Versace, 2022, Gigi Hadid@The Met Gala

Sources

The Corset, A Cultural History, Valerie Steele

FASHION, Die Sammlung des Kyoto Costume Institute, Eine Modegeschichte vom 18. bis 20. Jahrhundert

Wow, what an insightful and beautifully written piece on corsets! Your passion for this timeless garment shines through in every word. I appreciate how you've not only delved into the history of corsets but also highlighted their modern resurgence, emphasizing the empowerment and self-expression they can bring. The way you describe the intricate details and craftsmanship involved in creating a corset truly adds an extra layer of appreciation for this art form. Your blog has not only educated me but also ignited a newfound admiration for the beauty and versatility of corsets. Thank you for sharing your expertise in such an engaging and informative manner. I'm looking forward to reading more from you!